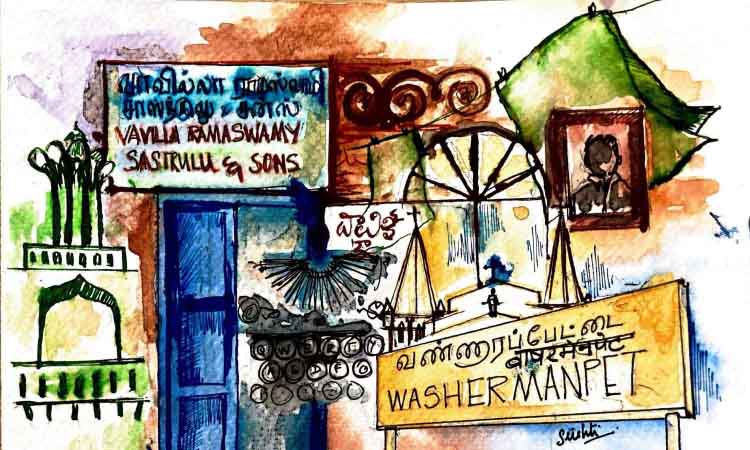

Chennai: A maze of narrow lanes leads to Washermanpet or Vannarappettai, which began along the waters of the Ellambor and Buckingham Canal, where washermen would spread white calico to dry in the sun. This utilitarian beginning, marked by the Company’s cloth trade, laid the foundation for a locality that always worked with its hands. By the end of the 19th century, the pulsation of industry soon began to grow: the clang of hammers resounded in the metal workshops, textile depots flourished and women’s hands in beedi factories were busy wrapping tobacco leaves into packets for export. What was once marginal land turned into the bustling centre of Vannarappettai, thanks to its proximity to the arteries of the port and Royapuram. As the city grew beyond its rivers and canals, the railways arrived, and with them the Basin Bridge junction became the beating heart of north Madras. From here rail lines stretched out towards Royapuram, Vyasarpadi and the port, carrying both people and goods. For many families here, the railway yards and workshops meant steady jobs and a daily rhythm defined by whistles and signals. Washermanpet emerged as a working-class bastion, its streets alive with unions, artisan trades and printing entrepreneurs. Ramanujam Street is home to the Vavilla Press, established in 1854, which once dared to publish Muddupalani’s bold Telugu poem on sexuality, Radhika Santhavanam, which gave rise to India’s first obscenity trial. The devadasi poet’s poems, defended decades later by Bangalore Nagarathnamma, became part of the city’s feminist and literary history. Not far from here is Sir Theagaraya College, named after Justice Party leader Sir P Theagaraya Chetty, whose politics shaped early 20th-century Madras. Its halls welcomed the first generation of learners from north Chennai, spreading education to a working-class locality. The Bavutha Bidi Company, started in 1905 by Sheikh Ismail, once shipped chocolate and vanilla flavoured bidis made by the nimble fingers of Muslim women across the sea. In another lane, a desperate mother carved a statue of the deity Mariamman out of sand to pray for her daughter’s health; the temple still stands, tended by women priests. The St Roque Church, built in 1814, arose from a Catholic cemetery whose Luso-Indian families linked Portuguese memory with Tamil soil.

Washermanpet flourished not just as an economic hub, but also as a political platform. It was here that CN Annadurai mesmerised crowds at Robinson Park (now Anna Poonga), and founded the DMK in 1949, a defining moment in Dravidian politics. Today, the metro brings people to the farthest reaches of Chennai quickly. It is a transformation that points to a new future, even as the lanes still reverberate with the language of cricket, the smell of street food and the hum of trade in Madras Bashai. What began as bundles of calico on the riverbank now runs on steel tracks, yet Washermanpet’s pulse has never stopped. In many ways, its shape reflects Chennai’s transformation from colonial Madras to a city that is connected, struggling and constantly being remade. Its streets tell a story of labour and voice, neglect and renewal, and pose an urgent question for planners: by threading it into a network, can we avoid erasing its vibrant fabric?