Unchecked Pilgrimage, Construction In Uttarakhand Spell Disaster For Fragile Himalayas, Warn Experts

Crumbling mountainsides, sinking towns and untrammelled construction. It is against this backdrop that thousands of pilgrims make their way to the upper reaches of Uttarakhand each day, posing serious risk to the fragile Himalayan region, say experts. That reports of landslides are increasing and people in subsidence-hit Joshimath, the gateway to Badrinath, one of the Char Dham destinations, are being compelled to move back to the homes they left because of large cracks add to the general sense of foreboding gripping the area.

Environmentalists point to the road expansion project as another factor posing a serious risk to the stability of the region, already highly prone to climate-driven disasters, experts say. The Uttarakhand government’s decision to lift the daily cap on the number of pilgrims visiting the state for the Char Dham Yatra is a matter of grave concern, according to environmental activist Atul Sati.

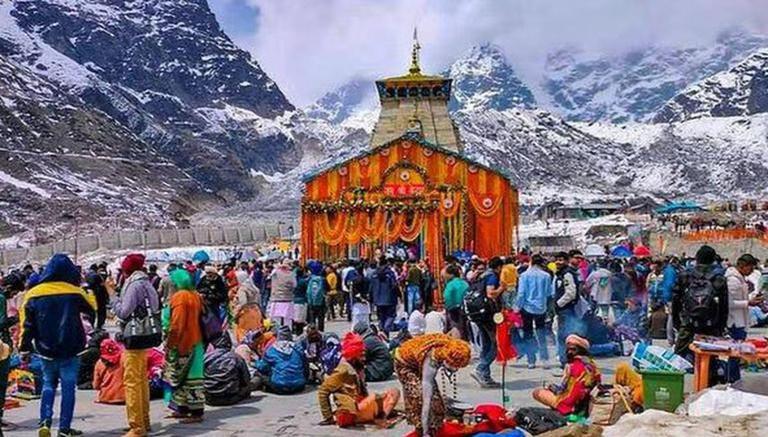

Earlier, the daily limits were — Yamunotri (5,500 pilgrims), Gangotri (9,000), Badrinath (15,000) and Kedarnath (18,000). “The increasing influx of thousands of pilgrims per day to Badrinath and other pilgrimage sites, along with a surge in the number of vehicles and heedless construction projects in the vicinity, is posing a significant threat to the ecological and biological diversity of the region,” Sati told PTI.

“On May 4, a mountain crumbled in Helang on the way to Joshimath while road widening was taking place. After Joshimath, the land is sinking in many other places in Uttarakhand. Every day we hear about people losing lives due to landslides on the roads,” he added. Geologist C P Rajendran said the attendant problem of higher footfall is the generation of huge amounts of waste, including plastics and horse and donkey excreta.

The heavy pilgrim traffic, he explained, could also result in the melting of glaciers and environmental degradation with a serious impact on biodiversity. “Many higher altitude areas in the Uttarakhand Himalayas host rare medicinal plants that are facing serious extinction threat due to climate change coupled with the dumping of waste,” Rajendran told PTI.

A 2019 report headed by veteran environmentalist Ravi Chopra described the Char Dham project — an ongoing road project that will connect the four important pilgrim towns of Badrinath, Kedarnath, Gangotri, and Yamunotri — as “an assault on the Himalayas”. The committee recommended limiting road widths to 5.5 meters on the Char Dham project. However, in December 2021, the Supreme Court in its order allowed the road width to 10 meters.

Environment researcher Abhijit Mukherjee noted that a primary reason for landslides in the Himalayas is because road widening cuts away the toe of slopes that support the rocks. This in turn destabilises the mountain area. “I would imagine the mega-road constructions going on in the surrounding of Char Dham have certainly developed such ill-supported slopes which are absolutely prone to sliding and sinking,” Mukherjee, professor of Geology and Geophysics at Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Kharagpur, told PTI.

He explained that several hydropower projects being built in the Uttarakhand-Himachal Pradesh region in recent times involve building a dam or barrage, and this has its own perils. “While these dams or barrages are important to engineer the river by building a reservoir, what it also does is disturb the natural hydrologic equilibrium of the slopes with the rivers,” he added.

Sati said reports of accidents have increased due to continuous stone shooting and mountain crumbling. “It is more important to make traffic safe than widening the road,” he said. In his view, authorities have not taken adequate measures to address the environmental and safety concerns of both the pilgrims and the local community.

Adding a note of warning, Rajendran said the mountains, already dealing with forest fires, deforestation, loss of water sources, and soil loss, cannot bear the brunt of “unregulated tourism and footfall”. On January 2 this year, hundreds of people were displaced by a land subsidence event in Joshimath town and forced into relief camps.

Experts as well as locals attributed the event to unscientific road construction and infrastructure projects coming up in the ecologically fragile zone. A study published earlier this year estimated that 309 “fully or partially road-blocking landslides” were identified along the 247-km road stretch between Rishikesh and Joshimath, which translates to an average of 1.25 landslides per km.

According to environmental expert Anjal Prakash, there is need for a regulated system based on the carrying capacity of the hills. “The hills have their own carrying capacity. Water supply is limited, and people run out of water, and sanitation is problematic at times. Definitely, the number of people visiting should be regulated, but the regulation has to be oriented towards people,” said the associate professor (research) and research director, Bharti Institute of Public Policy, Indian School of Business (ISB), Hyderabad.

Uttarakhand has a long history of natural disasters, including earthquakes, landslides, cloud bursts, and flash floods that have claimed thousands of lives in the past. Over 1,000 people were killed in such extreme weather events between 2010 and 2020. Many villages in the state have been marked unsafe for living.

The 2013 Kedarnath flood, which killed over 6,000 people, was a wake-up call, said Rajendran. “The intensity of this disaster was directly proportional to the unregulated rise in tourism that led to a construction boom in unsafe zones such as the river valleys and floodplains and slopes vulnerable to landslides, violating laws on land use,” said Rajendran.

Sati said the impact of climate change is already being felt in the mountains of Uttarakhand, with unseasonal rains and snowfall creating difficulties during the ongoing yatra. “Every day we hear about people dying on the way to Badrinath due to landslides. If we keep up with our unscientific ways of destroying nature, it will only lead us to a bigger catastrophe,” he warned.

Mukherjee also criticised the lack of respect for scientific knowledge in most development projects in India. “The utter disrespect for science from the top administrative level to local contractors has led to discontinuity in background scientific study-led decision-making. Any of these big projects, missions, activities, plans should have been based on scientifically-prudent decisions… longer, sustainable development can be definitely done,” he said. The Char Dham are situated at a considerable height with Yamunotri at an altitude of 3,291 metres, Gangotri at 3,415 metres, Kedarnath at 3,553 metres, and Badrinath at 3,300 metres.