This is the first Ramzan that 34-year-old Ayesha Izhaar is offering namaz at the mosque. The Bengaluru-based teacher would regularly offer her prayers at mosques when she was living in the UK as a student but back home, options were limited. “I could not understand why I could offer namaz in mosques in a western country with a much smaller Muslim population, but not at home,” says Izhaar.

Through the Muslim Women Masjid Project (MWMP), which fights for accessibility to places of prayer, she finally got to know about a mosque which had a separate section for women to offer their prayers. “In November 2022, I visited a mosque in JP Nagar. I was amazed by the number of women who had come from all economic stratas,” Izhaar recalls. Since then, she has found a mosque closer home, and goes every Friday. During Ramzan, the festivities are heightened, and Izhaar has made friends in the mosque. They discuss faith, but also their lives, careers, and education.

The MWMP is helping many others find women-friendly mosques by making a list across 15 cities in India. The team also conducts coordinated visits to different mosques, and regularly holds discussions with local masjid committees to ask for better facilities for women. The seeds for this were sown in a study circle for Muslim women, started by Sania Mariam in 2020. The circle was initially formed to discuss religious and academic texts. In one such discussion, however, the participants started talking about the limited access to mosques for Indian women. There was an outpouring of emotions and several women recalled their experiences of offering namaz in mosques abroad. “We then started questioning why similar options do not exist in India,” says Mariam, who’s currently pursuing her PhD in international relations.

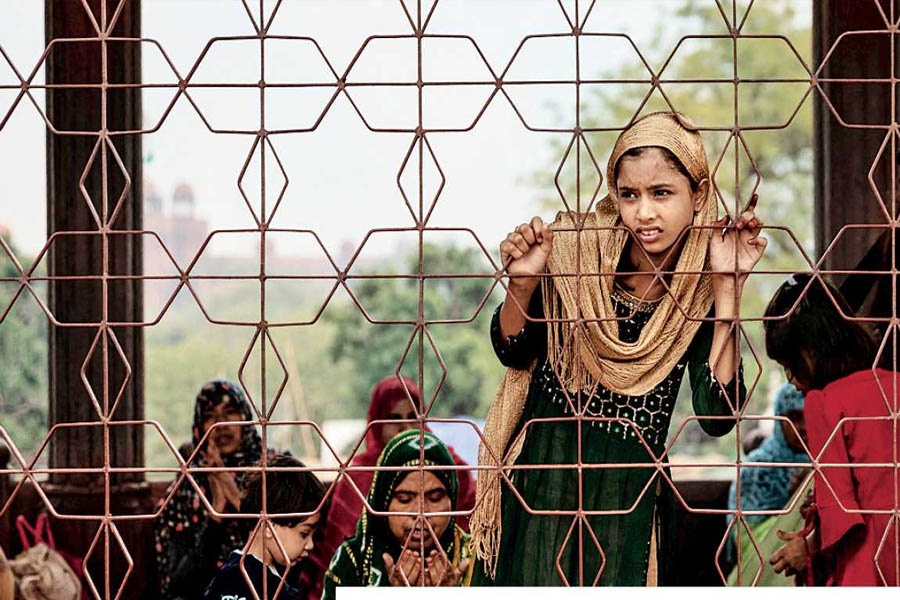

Winds of change are blowing across the country. In February, the All India Muslim Personal Law Board told the Supreme Court that the entry of women in mosques was permitted. In March, in a historic first, the Aishbagh eidgah in Lucknow created a separate section for women to offer tarawih. Tarawih refers to nightly prayer during Ramzan, which involves reading long portions of the Quran and performing cycles of movement.

“While it’s not possible for small mosques to create separate sections for women, we realised that the eidgah was big enough to do that,” says Maulana Khalid Rasheed Farangi Mahli, the imam of Lucknow Eidgah and chairman of the Islamic Centre of India.

He adds that ever since the announcement, women have come in huge numbers to offer their tarawih at the eidgah, adding to the spirit of Ramzan festivities. “Koi naya step hota hai toh uspe initially ungliyaan toh uth ti hi hain (when you take a new step fingers are raised initially),” he adds. However, he is undeterred by the opposition and plans to push for a facility for women to offer jummah prayers.

Elsewhere, the struggle is taking other forms. In Kerala, Huda Ahsan, director of the Khadija Maryam Foundation, is leading the charge to create a women-only mosque. In the planned mosque, the imams, devotees and committee members will all be women.

“We didn’t want the token gesture of someone allowing us a small space in a mosque or anyone’s sympathy,” says Ahsan, who first ideated the mosque as part of her architectural thesis project. The process of raising funds for the construction is underway.

Making the space exclusive to women, Ahsan adds, was a crucial step in ensuring that decision making power is not usurped by the men. “We wanted to make it clear that we don’t need anyone’s permission to do this.”

MWMP has a different approach, opting to counter resistance within the community through dialogue. Ayesha Manzoor, the Assam coordinator for the project, says even among the women who came to the mosque, there were doubts about whether this was permissible under Islam. In order to quell such doubts, Manzoor and others have turned to citing scholarly works.

One such work is Ziya Us Salam’s book ‘Women in Masjid: A Quest for Justice’, first published in 2019. “As far as women’s entry into mosques is concerned, there is not one verse in the Quran that prohibits women from going to mosques. They have merely been exempted from going to mosques compulsorily and been given a choice. It’s as simple as that,” Salam explains.

“However, in our country, it seems a man’s prayer is more important than a woman’s prayer,” laments Salam, a long-term advocate for greater accessibility of Muslim women to mosques. While maulanas themselves take their wives along on umrah to Mecca, he writes in the book, they come back to India and oppose their entry to mosques. Challenging this dichotomy, therefore, is crucial to the fight for greater accessibility. He also adds that guidance given to the community, an important part of sermons in mosques, would be meaningless if they excluded half the community.

In terms of facilities, creating women’s sections in mosques will not be enough. “Mosques also need to create a separate space designed for women where they can wash themselves. Just like there are spare caps for men, there should also be spare hijabs for women who wish to cover themselves,” Salam adds.

Mariam also complains about the lack of facilities. “Even though some mosques have sections for women, they are largely very congested and unkempt and the quality of washrooms or audio systems isn’t proper.”

While the roads taken by women across the country are different, they all lead to the same destination: a right to pray publicly, safely and freely.