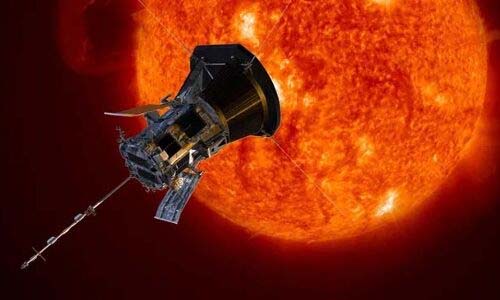

Parker Solar Probe set to fly past the Sun on Christmas Eve

Science: On Christmas Eve, NASA’s Parker Solar Probe will pass 3.8 million miles (6.1 million kilometers) from the sun’s surface at a speed of 430,000 mph (690,000 kilometers per hour), breaking its own records for speed and closest approach to our star.

The spacecraft, which is about the size of a small car, completed its final orbit past Venus last month, putting it on track for the closest approach to the sun than any human-made object.

On Dec. 24, Parker Solar Probe is expected to cut through clumps of plasma that are still attached to the sun and even fly through a portion of the solar eruption, much like a surfer diving beneath a crashing wave. In October, the sun reached its most turbulent phase in its 11-year cycle, meaning the spacecraft will soon study powerful solar flares that occur one after another, providing scientists with up-close data about the chaotic workings of our star.

“We are preparing to make history,” Noor Rawafi, the mission’s project scientist, told reporters at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) on Tuesday (Dec. 10). “Parker Solar Probe is opening our eyes to a new reality about our star,” he said, adding that the data sent home by the probe “will take us decades to sort through.” The probe’s achievement is expected at 6:40 a.m. EDT (1140 GMT) on Christmas Eve, but mission control will not be in contact with the spacecraft at this time. Shortly before and after closest approach — on Dec. 21 and Dec. 27 — scientists will look for a beacon tone from the probe that will confirm its health.

If all goes according to plan, the first images from the encounter could arrive as early as the new year, and science data will follow in the weeks after that, Ravafi said. Since its launch in 2018, the probe has helped solve long-standing mysteries about our star, chief among them how its tenuous outer atmosphere, the corona, gets hundreds of times hotter as it moves away from the sun’s surface. In 2022, the probe’s coincidence with Europe’s Solar Orbiter spacecraft gave scientists a rare opportunity to study the same part of the solar wind, revealing how energy-packed plasma waves accelerate the solar wind to unexpectedly high speeds.