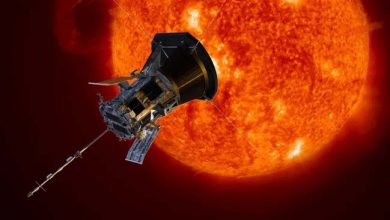

Lava helps James Webb Space Telescope discover watery exoplanets

Science: One way to find water worlds beyond our solar system might be to look for minerals — or more specifically, to study the minerals mixed in with cooled lava on exoplanet surfaces. That’s because if water comes into contact with fresh lava in the process of cooling, it can promote the formation of specific minerals within the lava. So, find those minerals, and you can get closer to the water that created them — whether that water is on an exoplanet’s surface or hidden underground.

Of course, this concept assumes that some exoplanets actually have cooled lava that can be detected with our instruments — and therefore have displayed volcanic activity at some time in their past — but the odds are in our favor. Within our own solar system, we’ve seen lava flows on Mercury, the Moon, Mars, and Jupiter’s moon Io. Any rocky world is likely to have been a volcanic world at some time in its history.

Thus, a team of researchers recently created a database detailing how certain minerals in cooled lava on a planet might reveal themselves to one of astronomy’s most powerful instruments: the James Webb Space Telescope. The study team decided to focus their attention on a substance called basalt, because this dark, fine-grained rock forms when lava flows onto a planet’s surface and then cools. It’s one of the most common rocks in our solar system — and probably in the rest of the galaxy, too. “We know that most exoplanets will produce basalt,” Esteban Gazelle, an engineer at Cornell University and co-author of a study about the database, said in a statement. Gazelle further explained that the chemical composition of most of the stars we’ve discovered suggests that planets should be made of the right ingredients to produce basaltic lava: “It would be prevalent not just in our solar system, but throughout the galaxy.”