Bootleg histories create new rifts and villains

Future historians writing of this time may well conclude that the defining battle of brave New India wasn’t fought against unemployment or malnutrition, nor against pollution or climate change, but against the Mughals. It is a belated campaign — the Mughals having marched across the Indus, settled in Hindustan, built one of the greatest empires the world has ever known and suffered the decline that is the fate of all power long before New India turned against them. Nonetheless, the campaign is vociferous, whether brandishing paintbrushes to rename streets or disembowelling textbooks.

The NCERT textbooks that were thus ‘rationalised’ a year ago will now begin to be used in schools. Part of this ‘rationalisation’ — an Orwellian term if there ever was one — has been to delete a chapter on the Mughals from a textbook for class 12. It is almost poetically ironic that the chapter is titled ‘Kings and Chronicles’.

Kings have, indeed, long produced chronicles to document and justify their reigns, and the early Mughals did so with more flair than most. Both Babur and his great-grandson Jahangir wrote remarkable histories of their own lives and times; Babur’s daughter Gulbadan wrote a plainspoken account of her brother Humayun’s travails. Her ‘Humayun-nama’ was commissioned by Akbar, in fact, as part of a larger project of history-writing that resulted in the monumental ‘Akbarnama’ by Abul Fazl, which is both an account of Akbar and his dynasty and provides the ideological foundation for its rule.

Not surprisingly, Abul Fazl occupies pride of place in ‘Kings and Chronicles’ — but the chapter also includes sections on painting, architecture, and other ways in which the Mughal state crafted and communicated its vision of itself. This vision rested, as the chapter begins by saying, in the Mughals’ belief that they were “appointed by Divine Will to rule over a large and heterogeneous populace” — and it was a vision that was so successfully realised that, as the chapter concludes, the dynasty “continued to enjoy legitimacy in the subcontinent… even after its geographical extent and the political control it exercised had diminished considerably.”

You could argue, of course, that these chronicles — certainly the chronicles of Abul Fazl — were state-sponsored projects. Indeed, the ‘Akbarnama’ is neither a personal account nor an academic history, collecting and measuring evidence in the hope of producing verifiable ‘fact’. State-sponsored history of this kind — of the kind, in fact, that the NCERT, being an organ of the state, was constituted to produce — may well contain facts, but it aims to convey something larger, a ‘truth’. Thus “Mughal chronicles”, the deleted chapter says, “present the empire as comprising many different ethnic and religious communities — Hindus, Jainas, Zoroastrians and Muslims. As the source of all peace and stability the emperor stood above all religious and ethnic groups, mediated among them, and ensured that justice and peace prevailed. Abu’l Fazl describes the ideal of sulh-i kul (absolute peace) as the cornerstone of enlightened rule.”

This unifying imperative was not unique to the Mughals; it has been a cornerstone of modern, nationalist histories, too — histories that allow a nation to feel a collective pride in its past. My own hazy memory of school history is of a series of great men and occasional women — from the Harappan architects and their clever drains to the leaders of the freedom struggle, from the Guptas and their Golden Age to heroines of the Chipko movement — all working doggedly towards the betterment of the Indian state. There were no villains — except Aurangzeb and the British.

Now we have nothing but villains, it seems — Jawaharlal Nehru and the Congress, even Mahatma Gandhi sometimes, and of course the Mughals. This new history for New India is not nationalist, in that it seeks to unite a nation under a benign if unwieldy banner. Instead, it seeks to turn certain political constituencies against others, to create grudges and sow division. Its reason for being is not to produce a new unifying truth, nor even to tell a subaltern history that moves the focus away from rulers to their subjects, but to correct the alleged ‘bias’ of leftist, ‘secularist’ historians in favour of Muslim kings — by amputation, it seems.

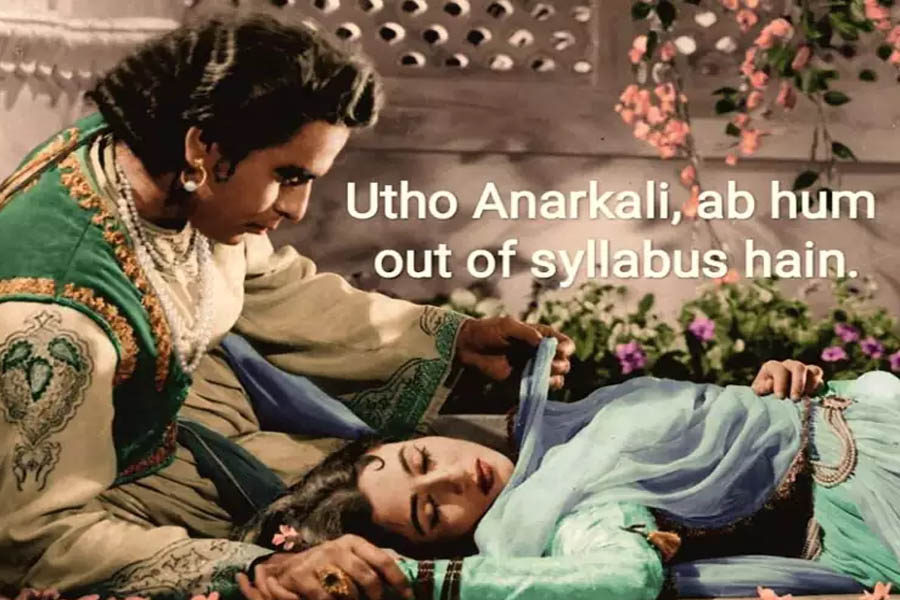

But removing the Mughals from textbooks to give more space to Hindu dynasties will not excise them from the Indian imagination — any more than prohibition has ever stopped people from drinking. Instead of the measured if sometimes dull prose of ‘Kings and Chronicles’ and its earnest exhortations to ‘discuss’ (‘Are some of the rituals and practices associated with the Mughals followed by present-day political leaders?’ for example), we will have bootleg history — laced with innuendo, falsehoods and angry emojis. Far from being asked to discuss things, we will be encouraged to seek revenge.

And so, far from learning that history is not an exact science, that it always contains bias, far from learning the value of scepticism — of critical thought, corroborative evidence, independent analysis — we will accept that not learning one kind of history or another is a virtue. In short, having drunk spurious liquor, we will become blind.