Astronomers: Black hole jet examined with the Event Horizon Telescope

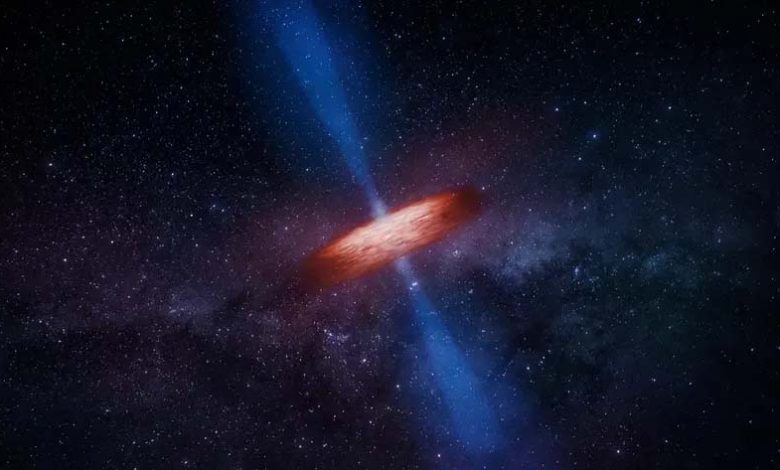

Science: Astronomers studying the elusive supermassive black holes at the hearts of galaxies are fascinated not just by these cosmic behemoths but also by the enormous jets they shoot out into space at nearly the speed of light, the largest of which extend millions of light-years. In particular, the physics of creating and accelerating these jets to near the speed of light is still unknown. A large group of astronomers led by Anne-Kathrin Baczko of Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden is now confident that the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) — a planet-sized array of eight ground-based radio telescopes built by an international collaboration — is up to the task. In 2017, the team used the EHT telescope for the first time to look into the dust-shrouded heart of a distant galaxy, where black hole jets form and pick up speed. The galaxy, NGC 1052, is located about 60 million light-years away in the constellation Cetus and contains a supermassive black hole that weighs more than 150 million suns and has bipolar jets emanating from its east and west sides when viewed from Earth.

Despite being a promising target for EHT imaging, the galaxy’s heart is “hazy, complex and more challenging than all the other sources we have tried so far,” Baczko said in a statement. “For such a hazy and unknown target, we weren’t sure we’d get any data — but the strategy worked.”

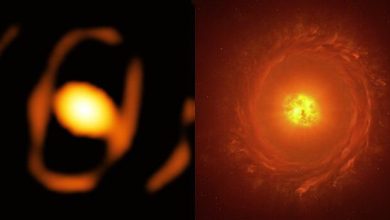

The team’s observations revealed that NGC 1052’s black hole region emits bright radio waves at a millimeter wavelength. This wavelength region on the electromagnetic spectrum is accessible by the EHT to create the sharpest possible images, according to a paper published recently in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

However, the region is even brighter at slightly longer wavelengths, making it a prime target for upcoming radio telescopes, such as the next-generation Very Large Array in New Mexico or the next-generation Event Horizon Telescope, an extended version of the EHT that astronomers hope will capture not just images of the black hole but video as well.

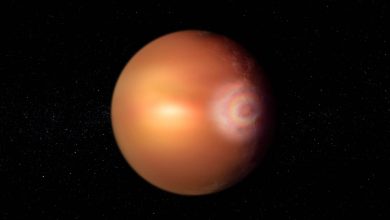

Meanwhile, the dusty region around the black hole, where the jets are generated, was found to be similar in shape to the ring around the supermassive black hole M87*, which became famous in 2019 when it became the first void to be imaged as a fuzzy orange donut by the EHT collaboration. Researchers say this means the region is “large enough to be easily imaged with the full power of the EHT.”